Painting & drawing blog

HOW TO READ A PAINT TUBE

The anatomy of a label

I have to admit that when I first starting buying paints as an art student, I chose them solely based on the colour swatch printed on the label. I really didn’t know anything about how paints were manufactured and the only other decision I’d make when buying a tube was to avoid the most expensive shades, since paints of all types vary wildly in price depending on the pigments they contain.

Since becoming a professional artist however I have learnt how to read all those mysterious labels and codes that you find on the label of a paint tube. I’ve found that doing so really helped me to select and apply my colours more effectively, and gave better long term, structural stability to my paintings. It was also an interesting insight into how paints are marketed to us as consumers.

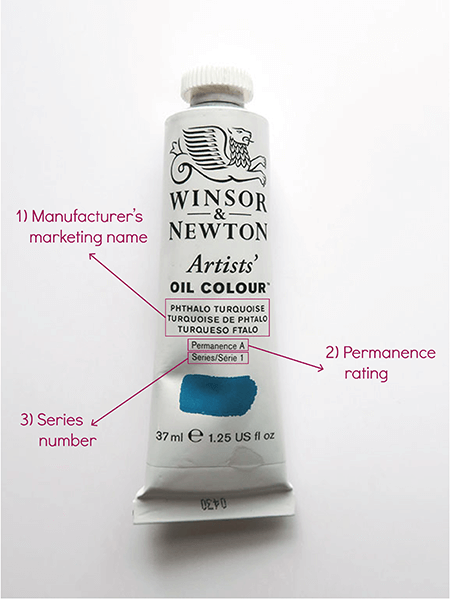

In this post I am going to explain all of the markings on the label of this tube of oil paint, but if you paint in acrylic, watercolour or gouache you’ll find all the same icons and codes on your tube.

1) MARKETING NAME

You might think that the name of the paint colour is so self-evident that it requires little discussion. However the name that the paint manufacturer gives to their product is likely to be the most misleading piece of information on the label! I call it the ‘marketing’ name because that’s really all it is: a name chosen by a paint company which does not tell you which pigment or combination of pigments the colour is made from.

To understand this we need to be aware of the difference between the terms ‘paint’ and ‘pigment’. The pigment is what gives the paint its colour. It will derive either from a ground organic substance, or a synthetic substance that is chemically produced. The paint is the combination of that pigment and a binder (such as oil, acrylic polymer or gum arabic) which holds the pigment together and dries into a film when you apply the paint to your paper or canvas. There may also be other additives included in the paint mixture such as drying agents or fillers to bulk the paint out. These additives do not have to be declared on the paint tube.

There IS actually a standardised scheme for naming different pigments. It’s known as the Colour Index, which we will discuss further below. However you’ll frequently find that the marketing name on the paint tube is not the same as the official name of the pigment it contains. In this case the only way to identify those pigments is to look for a little code on the back of the tube which identifies the colour according to the Colour Index.

With our oil paint tube above, the marketing name that Winsor & Newton have chosen is Pthalo Turquoise. This is a bit more helpful than many marketing names, in that it does at least tip us off that the paint has been produced with synthetic organic pigments from the pthalocyanine family.

However on checking the Colour Index codes on the back of the tube I can see that this oil colour hasn’t been made from one single turquoise coloured pigment – it actually contains a mixture of Phthalocyanine Green and Phthalocyanine Blue. In contrast Winsor & Newton’s Pthalo Turquoise shade from their professional watercolour range IS made from a single, purple-coloured pthalocyanine pigment. They are choosing to use the same marketing name for both paints, but the pigments that they contain are different.

The reason it might matter to know which pigments have been used to make your colours is that different pigments have varying properties that can affect how the paint performs in a number of ways. When the marketing name of the paint doesn’t help you to identify those pigments, you cannot anticipate how the paint will behave when you apply it and in the long term.

How do companies choose their colour names? In an ideal world the name on the tube would match the pigment used, but these pigments may have long chemical names that aren’t particularly catchy and have no romance to them. A manufacturer will also prefer a single name, whereas many paints – like our Pthalo Turquoise – are what are known as ‘convenience’ mixtures made from a number of pigments blended together to achieve a certain colour.

When a paint has a name that doesn’t trip off the tongue or doesn’t sound appealing from a marketing point of view, a manufacturer will come up with a more attractive one. Pthalocyanine Green pigment for example is sometimes sold as the simpler Phtalo Green but is also variously marketed as Sap Green, Rembrandt Green, or Winsor Green to name but a few examples.

Manufacturers like to come up with generically descriptive names like Brilliant Orange or romantic sounding but technically meaningless names such as Old Delft Blue. The prize for the most evocative names should surely go to Daniel Smith paints who are actually an excellent paint company known for developing new pigments particularly from mineral sources. They offer colours such as Imperial Purple, Lunar Blue, Aussie Red Gold and Sleeping Beauty Turquoise!

Paint companies continue to market paints with the names of pigments which are no longer used due to toxicity, lightfastness problems, environmental concerns or a simple lack of availability. For example Vandyke Brown and Naples Yellow were originally made from single pigments which are now obsolete. However most paint ranges still include a ‘Vandyke brown’ colour made by substituting one or more different pigments for the original lignite pigment, whilst Naples Yellow is now made with chromium titanate mixed with titanium white.

When paint companies produce a shade that is an approximation of a traditional colour in this way, they are supposed to add the word ‘hue’ to the name to make it clear that the colour uses substituted pigments, and so Vandkye Brown should really be described as Vandyke Brown Hue. In fact with very old colours such as Vandkye brown or Naples yellow where the original pigment fell out of use a long time ago, they rarely do this.

When manufacturers produce a colour that is an approximation of a more expensive single pigment colour that is still available, they do usually obey this best practice guideline and use the ‘hue’ description. For example, as an alternative to the very expensive Cadmium Red paint you will see a colour called Cadmium Red Hue which contains no true cadmium and is blended from a number of cheaper pigments. The resulting paint costs a fraction of the true cadmium paint.

2) PERMANENCE RATING

Our tube of paint has been given a ‘permanence rating’ of ‘A’. There’s no universal standard in permanence ratings and each company rates their paint according to their own criteria. Winsor and Newton’s letter rating system is as follows:

AA – Extremely Permanent

A – Permanent

B – Moderately Durable

C – Fugitive

Daler-Rowney paints use a ‘star’ rating system for permanence. Other brands (such as Royal Talens or Daniel Smith) may omit a ‘permanence’ rating and instead simply give a rating for ‘lightfastness’. Sometimes the two terms are used interchangeably.

These two terms – ‘permanence’ and ‘lightfastness’ – are confusing because they are not exactly the same thing. ‘Lightfastness’ purely describes a colour’s resistance to fading caused by UV light. ‘Permanence’ is a vague and general category, which takes into account not only the pigment’s resistance to exposure to light but also to other atmospheric conditions, as well as the chemical stability of the binder and the pigment over time. Winsor & Newton defines permanence as classifying “not only lightfastness but also the film & chemical stability of the paint”.

What I find unhelpful about the ‘permanence’ rating – despite the prominence that it’s given on the front of the tube – is that you don’t know exactly what reason the grade has been awarded. W&N further state that “For further information on some colours, the rating may include one or more of the following additions:

(i) ‘A’ rated in full strength may fade in thin washes

(ii) Cannot be relied upon to withstand damp

(iii) Bleached by acids, acidic atmospheres

(iv) Fluctuating colour; fades in light, recovers in dark

(v) Should not be prepared in pale tints with Flake White, as these will fade

(vi) ‘A’ rated with a coating of fixative”

From this I would surmise that if the permanence rating doesn’t include one of these extra category definitions -and I’ve never spotted one on a tube of Winsor & Newton paint – then it has been awarded purely on the basis of the resistance of the colour to fading.

Sometimes the lightfastness rating that’s given on the back of the tube doesn’t seem to accord with the permanence rating on the front. For example W&N’s Professional Water Colour Rose Dore colour is awarded a lightfastness rating of only ‘II’ and yet is given a permanence rating of ‘A’. In general, the top ‘AA’ rating is only awarded for the very stable ‘inorganic’ pigments derived from metal oxides such as viridian, cobalt, or titanium. Black pigments are usually also awarded an AA rating.

3) SERIES NUMBER

The last piece of coded information we are given on the front of our paint label is the ‘series’ number. This is a straightforward bit of information that tells you how much your paint tube is likely to cost. Manufacturers generally group their colours into five different price brackets or ‘series’. ‘Series 1’ paints will be made from the cheapest pigments and will be the least expensive in the range. Hue colours and most modern synthetic colours like our Pthalo Turquoise will be found in this band.

It doesn’t necessarily follow that a series 1 paint cannot be as good as one from a more expensive series – some pigments are just much easier and therefore less costly to produce or process. ‘Series 5’ paints are the most expensive and can cost well over twice as much as those in the Series 1 bracket. They are more likely to be derived from single pigments which are difficult and expensive to produce.

Let’s now take a look at the back of the tube:

4) COLOUR INDEX NAME/NUMBER

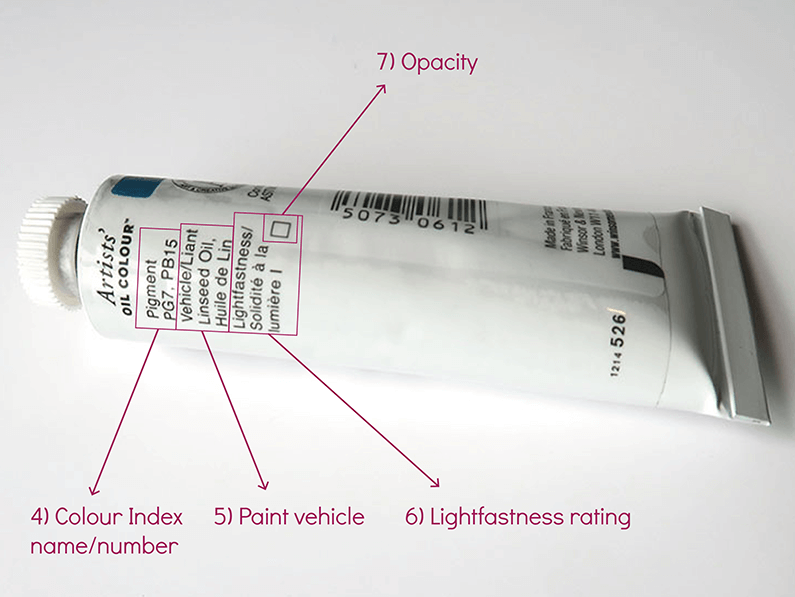

Turning over the tube, we finally find the only really useful information about what’s actually inside. This paint is listed as containing pigments ‘PG7 and PB15’. This information relates to the Colour Index which is a standardised naming system regulated jointly by the British-based Society of Dyers and Colourists and the American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists. You can find a useful version of this database for free here.

The Colour Index name is actually both an officially assigned name, and a code. The code is comprised of some letters and a number. The first letter will normally be a P which denotes that it’s a pigment (rather than a dye, for example) and then there will be another letter denoting the colour category: R for a red, O for an orange, Y for a yellow, G for a green, B for a blue, V for a violet, Br for a brown, W for a white, Bk for a black and M for a metallic pigment. If a pigment derives from a purely natural source it may start with an ‘N’ for ‘natural’ instead of a ‘P’.

Following the letters, there will a number which defines the individual pigment within that colour category. For example our paint tube includes two pigments: ‘PG7’ which is the number for the green pigment Phthalocyanine Green, and ‘PB 15’ which is the code for the blue pigment Phthalocyanine Blue.

You may notice that this particular tube of paint doesn’t follow best practice and omits to list the official names of the pigments, giving only the code instead. This is more common on European-manufactured tubes than American ones and it’s frustrating since the consumer can’t be expected to easily identify a pigment from its index code without looking it up.

The index name/numbering system still isn’t a completely reliable guide to the colour in your paint tube, since the actual shade of the pigment may vary between paint companies depending on their manufacturing processes – even where the pigments are chemically equivalent. This is because the methods of producing them chemically can result in differences in the finished colour. Therefore, a company may also use the same pigment to produce two or more different shades. For example the pigment ‘PR108’ might be used to make both a Cadmium Red Orange and a Cadmium Red Purple.

5) PAINT VEHICLE

The term ‘vehicle’ refers to the ‘binder’ which is the medium that’s been mixed with the pigment. It’s the substance that has been added to bind the pigment together and to form a film that holds it in place. Since our tube contains oil paint the medium used is an oil: in this case, linseed oil. In acrylic paints the pigment is suspended in an acrylic polymer emulsion whilst in watercolour paints the binder is usually gum arabic or synthetic glycol. The ‘vehicle’ description on a tube technically also includes any dilutants which may be added if the binder used is too thick.

6) LIGHTFASTNESS RATING

The lightfastness rating on a paint tube which is supposed to give you an indication of how resistant the colour will be to fading from light exposure, is represented in different ways by different manufacturers. The most common way to represent lightfastness is with roman numerals (I, II, III, IV etc). Manufacturers who use this system (including Winsor & Newton) are usually not doing their own testing but are using testing results from the ASTM which we previously mentioned. The ASTM rating system is as follows:

I. Excellent lightfastness. The pigment will remain unchanged for more than 100 years of light exposure with proper mounting and display. (Suitable for artistic use.)

II. Very good lightfastness. The pigment will remain unchanged for 50 to 100 years of light exposure with proper mounting and display. (Suitable for artistic use.)

III. Fair lightfastness (Impermanent). The pigment will remain unchanged for 15 to 50 years with proper mounting and display. (“May be satisfactory when used full strength or with extra protection from exposure to light.”)

….and so continues down to V (very poor lightfastness)

Other rating systems may merge some of these categories to produce a system that divides lightfastness into just three categories with ‘I’ representing ‘Durable’, ‘II’ representing ‘Intermediate’ and ‘III’ representing ‘Fugitive’.

Some companies use different icons for lightfastness. Royal Talens uses a system of noughts and crosses (o, +, ++, +++) which runs in the opposite direction so that o is the least and +++ the most lightfast. Schmike uses a star system which also runs in this direction, with ★ indicating the least lightfast paint and five stars indicating the most lightfast.

In short, you’ll need to consult the manufacturer’s website to work out how to read their particular system, and to find out whether they are relying on the ASTM ratings or on potentially unreliable information given by the pigment manufacturer, or whether they are actually testing their own paints themselves. Very few paint companies test their own paints for lightfastness. Daniel Smith and Schminke are amongst the few who do so.

It’s unfortunate that so many manufacturers do not test each paint that they make for lightfastness because the lightfast qualities of a pigment are not set and unchanging. The ability of a pigment to resist light may depend on:

- How the pigment has been manufactured: how finely it has been ground, and so on.

- Which additives it has been mixed with in the tube.

- Which binder (oil, acrylic, watercolour etc) it is mixed with. For example, testing a pigment for its behaviour when suspended in an oil or acrylic solution doesn’t tell you how it will perform when made into watercolour. There is an ASTM test standard specifically for watercolour paints but only Daniel Smith paint state that they adhere to these ratings. Other watercolour paint manufacturers just show you general lightfastness ratings where the pigments may been tested in suspension with an oil.

- How the finished painting is displayed. ASTM lightfastness ratings relate to artworks kept in museum conditions, where light is controlled and reduced. This is very different to a painting displayed in someone’s home, as the ASTM admits.

Paint company Schminke who do test their own paints note the following:

The lightfastness tests are always run on the finished Schmincke colours, not on individual components of the formula. This is important for the simple fact that even those paints with extremely lightfast pigments may change colour if the wrong binders or additives were used. Thus, we don’t merely check how the pigment changes (colour fading), but can instead see the entire gamut of changes to the colour (darkening, changes in lustre, etc.).

Due to the way that paint manufacturers rely on different sources for their lightfastness ratings, you’ll see variability in the lightfastness ratings awarded to the same pigment by different companies. For example Winsor & Newton’s Potter’s Pink colour carries a lightfast rating of only II, whereas in Daniel Smith’s watercolour range the Potter’s Pink which is made from the same pigment (but presumably tested by the company themselves) is awarded a grade of I.

Where a company relies on ASTM tests there may not even be a rating awarded for certain new colours and you’ll sometimes see ‘N/L’ on the website chart for that colour which tells you it has not yet been tested by the ASTM. In this instance Winsor & Newton suggest that you:

“…refer to the Winsor & Newton permanence rating, which evaluates colour on many aspects including lightfastness and is used to indicate a colour’s ability to resist fading.”

Where does all this confusion leave us? If lightfastness is of concern to you – particularly if you are producing work to sell to the public – I’d suggest sticking to paints awarded only the top lightfastness rating. Paint companies continue to sell a number of highly fugitive colours such as Alizarin Crimson which is so lacking in lightfastness that it is considered by many to be unsuitable for artists to use. Be aware that the greatest risk for fading is when a small amount of a fugitive pigment is used, for example within a tint, mixed with white. This is likely to fade faster than a large mass of the pigment used by itself.

7) OPACITY

Some pigments are much more transparent than others. On our tube of Phalo Blue, Winsor & Newton indicates the level of transparency of the paint with a little empty box . This indicates that the colour is extremely transparent. A white box with a diagonal line through it would mean semi-transparent, a diagonally-divided half white/ half black box is used to indicate semi-opaque, and a completely black box would mean it was totally opaque.

Manufacturers find a variety of ways to indicate the degree of transparency/opacity of their colours. Sometimes a little ‘wheel’ icon is used. Other products employ a lettering system whereby transparent colours are marked ‘T’ and semi-transparent as ‘ST’, whilst opaque colours are marked ‘O’ and semi-opaque ‘SO’. Other manufacturers will keep things simple and just write ‘Opaque’, ‘Semi-Opaque’ and so on.

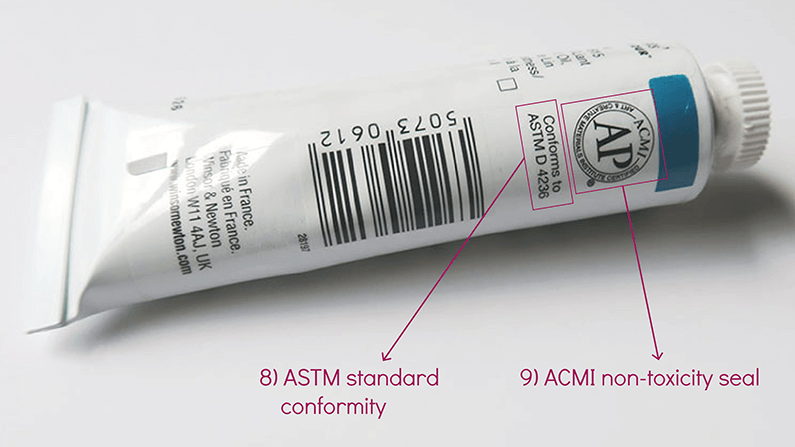

8) ASTM STANDARD CONFORMITY and 9) ACMI SEAL

Although our paint tube was manufactured by a British company, most European paints will indicate their compliance with American standards for paint labeling as regards health and safety. These codes are voluntary but have been widely adopted. Our label gives two of these common declarations. Firstly, it contains a written statement that the paint ‘Conforms to ‘ASTM D 4236’. This refers to ASTM’s Standard Practice for labeling Art Materials for Chronic Health Hazards guidelines. All this really means that any potentially hazardous ingredients or risks posed by the ingredients will be clearly labelled.

The second safety declaration is the seal of the Art & Creative Materials Institute or ‘ACMI’ which is an American non-profit association of art and craft supplies. An ACMI Approved Product Seal on a paint label certifies that the paint is non-toxic both children and adults and “contain no materials in sufficient quantities to be toxic or injurious to humans, including children, or to cause acute or chronic health problems”.

Inside this seal will be either a large ‘AP’ (for ‘Approved Product’) or ‘CL’ (for ‘Cautionary Labeling’). If there’s a CL label then underneath you’ll see a specific written warning about health problems posed by the pigment. For example my tube of Cobalt Violet watercolour paint has a CL label, and underneath a statement that the product may be harmful if swallowed and should be kept out of the reach of children.

© Article rights reserved. View this portrait artists work here

CATEGORIES

DRAWING PEOPLE

DRAWING ANIMALS

DRAWING MATERIALS

OIL PAINTING

WATERCOLOUR

PAINTING MATERIALS

FRAMING