Painting & drawing blog

CHOOSING YOUR COLOURS FOR OIL PAINTING

Some advice for beginners

When you are starting out with oil painting and need to choose which colours to buy, how do you decide between shades that may appear very similar? Here I’m going to look at factors you may want to take into account when you decide which colours to purchase to create your palette.

Usually, you’ll find that the number of colours available to choose between will depend on whether you’re buying a cheaper ‘student’ range or a more expensive ‘artist’ grade range. This is because the better quality ranges will usually contain many more colour options. Beginner ranges will be much more limited. I’ll explain the reasons why different oil ranges and different individual colours may vary so wildly in price and ask whether you should avoid just choosing the cheapest options.

There are no paid links in this post! Just my own opinions.

Whether you decide to choose your paints from a beginners’ range or from an artist grade paint like these Michael Harding paints above, many beginners will start by buying a small boxed set of colours. This gives you a basic colour palette for less than you’d spend if you purchased the tubes individually, and if you don’t have very clear ideas about which colours you want to use yet then a set can be a good idea. However there will likely come a point as your painting develops when you’ll want to add to this selection.

Price differences and understanding colour names

What makes one colour so much more expensive than another even when it’s part of the same paint range, made by the same manufacturer? This price difference will always be due to the particular paint pigment that has been used to make the colour. We should make the important point here that the ‘marketing name’ of the colour does not usually tell you which actual pigment (or pigments) the colour has been created with. Therefore for example an oil paint colour labelled as Indigo may be created using quite different combinations of pigments depending on which manufacturer has produced it.

Similarly, an identical pigment can be sold under quite different marketing names, by different manufacturers. Paint companies simply choose a name for the pigment that they think will be appealing. For example the pigment ‘pthalocyanine blue’ may be sold as Pthalo Blue but is also sometimes called Winsor Blue. It should also be noted that even paints made from the same pigment can have considerably different shades, depending on the production methods used to process it.

‘Series’ numbers

Pigments may be made from either organic or synthetic sources and can vary hugely in price depending on how rare they are, how difficult to extract or mine or how complex to manufacture chemically. This will affect the price of the finished paint tube. Paints are divided between four price brackets and given a series number to identify them which will be printed on the front of the tube. Series 1 paints are the least expensive whilst series 5 is the most expensive price band. Within a student grade range you’ll find the least variation in prices and are unlikely to come across any series 3, 4 or 5 colours.

Is a more expensive colour always better than one made with a cheaper pigment? The answer is not necessarily, because some perfectly good pigments may simply be quite cheap either to manufacture. In a better range of oil paints however you’ll find colours priced within all five series brackets. When a brand offers no higher series colours, this is a bit of a red flag because it suggests that the manufacturer has used entirely cheap pigments including in cases where better ones might have been substituted.

‘Convenience’ and ‘hue’ colours

One difference between cheaper and more expensive paints is that the better ranges will offer many more colours which are made with just one single pigment. A ‘single pigment’ colour will usually give you a more vibrant shade than one made up from a number of different pigments, which can go a bit ‘muddy’ when mixed with other colours. Often manufacturers will create ‘convenience’ colours made from several pigments, where no single pigment produces the shades that they want to offer. Many green colours are convenience mixtures.

Often a convenience mixture is produced in order to offer a shade that is similar to one traditionally made from a single much more expensive pigment, or one which is now either hard to obtain, environmentally unfriendly or potentially toxic. This kind of mixture is called a ‘hue’ colour and usually blends several cheaper pigments together. Cadmium Red Hue for example is often offered as an alternative to expensive pure red cadmium, but it contains no cadmium pigment.

Hue colours may sometimes be a fairly close match to the original colour, but often they don’t resemble it very well. Student grade paint ranges will be full of hue colours, whereas artist quality ranges will have small numbers of hues and may restrict them to single pigment alternatives. For example good oil ranges will commonly offer a Manganese Hue made from a pigment from the phthalocyanine family as an alternative to the original manganese pigment, which is now obsolete due to cost and environmental concerns.

Although it’s considered best practice for paint manufacturers to always use the word ‘hue’ in the names of appropriate colours, in fact not all will do so. There are also some famous colour ‘names’ which are approximations of a colour made a long time ago with pigments which are now no longer used and should strictly speaking be called ‘hues’. Vandyke Brown is one example: hardly any manufacturers use the original lignite pigment that was mined to produce this well known shade, so any shade called Vandyke Brown is really a hue imitation. Generally however aside from various anomalies, most reputable paint companies will use hue descriptions appropriately.

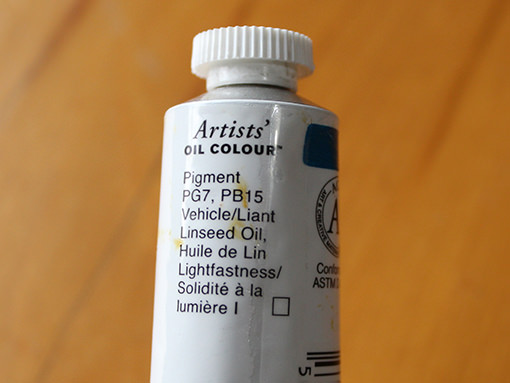

Working out whether a colour is made from a single pigment or a convenience mixture is hard to do. The only way to tell which pigment a paint contains is usually to look on the back of the tube (or on the manufacturer’s or retailer’s websites) for a tiny code beginning with ‘P’ for ‘pigment’ or sometimes a ‘N’ if it’s a natural type of pigment.

This code relates to an internationally recognized ‘Colour Index’. The index identifies colours firstly with the letter P, followed by one of ten colour categories: R for red, O for orange, Y for yellow, G for Green, V for violet, Br for brown, Bk for black, W for white and M for metallic. The final part of the code is a number that corresponds to the listing for that pigment within the index. For example, the index name for cobalt blue pigment is ‘PB28’.

If you want to know exactly which colour your paint contains you can find the code on the tube and consult the colour index here. This is something that you’re likely to want to do as you become more experienced – in fact many professional artists will choose colours based on the pigments they contain, as much as the manufacturer who produces them.

However even when you are starting out, it’s useful to understand that the more ‘P’ codes on the back of your tube, the more pigments have been blended to make that particular colour. If you are happy to use a paint colour straight from the tube then buying a convenience colour is fine if you like the shade and find it vibrant enough. However if you want to mix several colours together then using single pigment colours will create a colour with more clarity.

Artist grade vs student grade?

Before we move on to individual colours, lets at some differences between student and artists’ grade oil paints that you might want to take into consideration when deciding on a paint range to buy.

How can you tell whether a paint range is student grade? The price is pretty much always going to be the giveaway, although sometimes the name will include something like ‘Graduate’, ‘Studio’ or ‘Akademie’ which will tell you that it’s being marketed at beginners. Be aware that many manufacturers produce both an artist’s grade paint and a student grade paint and so you’ll need to choose not only between a company but also between their various ranges.

A top grade range will give you a much more intense colour than a cheap paint because not only will it use better pigments but it will include much more pigment in each tube. Premium quality oil paint may contain 80% pigment, mixed simply with an oil such as linseed or safflower to bind it and a tiny amount of additives to stop the pigments clumping together. The pigments will be ground to an optimum size to produce the maximum radiance obtainable for each. Some modern, synthetic organic pigments that have a very high ‘tinting strength’ (tinting means mixing a colour with some white in order to lighten it) such as the phthalocyanines may require some additional bulking agents to temper their strength, but these are not added in order to produce the manufacturing cost.

In contrast cheaper oil paints will contain as little as 23% pigment, derived from less expensive sources. It will also contain a similar ratio of oil, and tons of fillers used to extend the paint just in order to fill up the tube. All the additives and fillers in a cheaper range can give the paint a dull and even slightly chalky appearance.

The pigments will be ground uniformly and not as finely as with a professional paint, and various additives will be included to ensure that all the colours within the range have the same viscosity and dry at similar rates. This consistency of texture and drying times across a range is not considered important in a professional quality range where you’ll find that your colours feel different depending on the pigments they contain and will dry at different speeds.

Should you buy ‘student’ or ‘beginner’ grade paints when you are starting out with oil painting? Obviously everyone has to set their own budget as oil paints are not cheap, but I’d encourage you to buy the best that you can afford because you’ll get nicer results with them and will probably enjoy using them more. Having a smaller range of better quality colours and doing more mixing might be better than having a larger collection of cheaper tubes. You’ll get more intense and pure colours, a much nicer and more buttery texture, and a paint that mixes better, tints without losing its strength and goes further.

WHAT TO LOOK FOR WHEN SELECTING INDIVIDUAL COLOURS

Pigments vary in many ways. Some will dry much faster than others. They will have different degrees of transparency, of lightfastness (how well they withstand fading caused by UV light) and general chemical stability. In terms of choosing a basic palette of colours it’s hard to offer a prescription because it depends so much on what style of painting you are doing and what your subject matter is.

However it’s very useful to learn to read a few of the mysterious icons on the reverse of a paint tube in order to check the individual qualities of the paint colour you are considering. There are also a number of pigments I’d suggest avoiding altogether, if the longevity of your work is a concern.

How to check for lightfastness

A paint colour’s resistance to fading is difficult to assess, despite the presence on every tube of a ‘lightfastness’ value given as an indicator as to how quickly the pigments within it may fade. This value is typically given as a rating of between either I and III, or I and IV, depending on the paint range. In these schemes I represents the most lightfast colour. It’s often surprising to beginners that paint manufacturers continue to sell paints made with highly ‘fugitive’ pigments and therefore it’s always worth checking the tube to see which rating they have given to a colour.

In fact these lightfastness ratings are very problematic because rather than test their own paints manufacturers frequently rely on ratings awarded by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) or by testing done by the pigment manufacturers themselves. These tests may be lacking in specificity and sensitivity.

Part of Anne Dashwood (1743–1830), Later Countess of Galloway by Sir Joshua Reynolds 1764

Photo credit: Metropolitan museum of art (public domain)

In an ideal world every paint colour produced by a manufacturer would be tested individually, because its lightfastness will also be influenced by how the pigment has been milled and which additives it has been mixed with. People often ask how quickly oil colours can potentially fade and this is a different question to answer because it’s so variable. This work by Joseph Reynolds that demonstrates how a pigment (in this case carmine) can appear to vanish altogether, especially when used within a ‘tint’ to create a skin colour.

Would this kind of fading take centuries to happen? I would say no, and that you could easily experience quite a degree of fading within only a matter of decades with certain fugitive colours that are still widely sold. If you hang a picture onto a wall that receives strong direct sunlight, then it could fade even more quickly than that. In my experience the general belief that oil paints fade more slowly than watercolours does appear to be true, but even so if you are concerned about your oil paintings enduring for more than 10 years or if you plan on selling them, then I’d suggest not using any paint colour with a lightfastness rating of less than ‘I’.

To confuse matters, many manufacturers also show a ‘Permanence’ rating (typically given as a grade between AA and D) which usually takes into account not only the ASTM rating but also the pigment manufacturer’s testing, and the film and chemical stability of the binder. I find permanence ratings very unhelpful because you don’t know which criteria have been taken into account when awarding them, and because they can sometimes appear inconsistent with the lightfastness rating – for example a colour might be awarded a II for lightfastness and an yet be given an ‘A’ for permanence.

You’ll notice that very few colours are awarded a permanence rating of AA, which seems to have been reserved for very stable inorganic pigments such as viridian and titanium. Most colours seem to be given an A rating but you’ll see quite a few awarded just a B grade, and personally I avoid these.

Watch out for certain colours which are made from pigments which are well known to be lacking in lightfastness. The most infamous is Alizarin Crimson (PR83) which despite being very fugitive is such a popular colour that Winsor & Newton still rather bafflingly include it within their boxed paint sets. Companies like Winsor & Newton have phased out most severely fugitive pigments but still continue to offer one or two such as Rose Madder genuine (NR9) or Opera Rose (PR122). You might also come across Gamboge yellow (NY24) or Aureolin yellow (PY40) which should also be avoided.

This isn’t an exclusive list of fugitive pigments at all, which is why I prefer to stick to those awarded the top lightfastness rating. Manufacturers make alternatives to some famously fugitive colours such as Permanent Alizarin Crimson or Aureolin New. These are really hues which utilise completely different pigments to approximate the original colour. Note that there’s no guarantee that a colour that describes itself as ‘permanent’ really is such, in the very long term. But it will certainly be much more lightfast than the original colour it has been designed to imitate.

Transparent vs opaque colours

Pigments vary greatly in their level of opacity and transparency. Synthetic modern pigments such as phthalocyanines which are used to make blue, violet and purple colours and red hued quinacridones tend to be more transparent. So do some natural pigments derived from dyes, such as madders and the infamous alizarin crimson.The most opaque pigments tend to be the inorganic ones which are not based on carbon chemistry but are derived from natural minerals or ores. These include ‘earth’ colours, cadmiums, cobalts, chromes, whites and vermilion.

Does it matter whether your paints are more or less transparent? This really depends on the type of work you want to do. If you are painting big bold abstract shapes you might want to avoid paints which are very transparent. However if you want what you are painting to have some degree of reflexivity, then applying transparent or semi-transparent colours over opaque ones will allow light to bounce through them and create depth and glow.

Most manufacturers will indicate the degree of transparency on a tube of paint with a little square icon. A white square indicates an opaque paint, an empty square tells you it’s a translucent colour. A half white square stands for semi-opaque whilst an empty square with a diagonal line bisecting it indicates that the paint is semi-translucent.

Some things to know about white oil paint

Now that traditional white oil paint made from toxic lead is more or less obsolete, all white oil paint you’ll come across in an art store will be made from either titanium, zinc oxide, or from a combination of both. The two pigments are very different because titanium gives a strong and opaque colour whilst zinc is very transparent. Zinc also dries much more quickly.

Recently concern has arisen about the stability of zinc which becomes brittle with age and can cause cracking in the layers above it. Therefore be careful not to use great deal of pure Zinc White in any lower layers if you’re concerned for your paintings to last the test of time.

You can buy an ‘Underpainting White’ from most oil paint ranges to use for your lower layers which is formulated with titanium and a suitably low percentage of zinc, to speed up the drying a bit. This paint won’t contain enough zinc to cause any problems. White paint is usually bound with safflower oil instead of linseed oil, because the latter tends to yellow as it dries. However with an underpainting white, linseed oil will be used instead because it dries more quickly than safflower oil. This is more suitable for a lower layer, because you want your lower layers to dry more quickly than those above them to prevent your paint from cracking as it oxidises.

For tinting your colours a ‘Mixing White’ which is also a combination of titanium and zinc is recommended. Ttitanium is extremely opaque and and if you tint with pure titanium paint you can end up with a chalky, pastel shade. Zinc is much more transparent and doesn’t overwhelm the colour that you are lightening. A mixing white will contain a good balance of the two. You can compare the effect of tinting with different white pigments here.

© Article rights reserved. View this artist’s oil portraits here

CATEGORIES

DRAWING PEOPLE

DRAWING ANIMALS

DRAWING MATERIALS

OIL PAINTING

WATERCOLOUR

PAINTING MATERIALS

FRAMING