Painting & drawing blog

CHOOSING PAPER FOR WATERCOLOUR PAINTING

Hot or Not? And other questions…

Although watercolour isn’t necessary the easiest paint to apply, I always think of it as a simpler medium to use than oils because it doesn’t involve mixing the paint with any spirits, drying oils, or other substances. You simply need to choose whether you prefer pans or tubes, pick the brand you want to try, and off you go.

In fact the aspect of watercolour painting where beginners often face the most difficulty is in choosing the paper they should work on. This is because particularly here in the UK, different types of watercolour paper are defined by a baffling lexicon of traditional terms that they probably aren’t familiar with. Here I’m going to try to de-mystify all the different options and help you choose the type of paper that will best suit your level of experience and the type of painting you want to do. This post doesn’t contain any paid links, only my own recommendations.

THE PAPER SURFACE: ‘HOT’ ‘NOT’ OR ROUGH’

The first decision you’ll need to make when choosing your paper is what degree of texture you’d like the surface to have. Watercolour paper is sold as either ‘hotpressed’, ‘coldpressed’ or ‘roughpressed’ and in the UK these types are usually known just as ‘Hot’, ‘Not’ and ‘Rough’.

‘Hot’ (hot-pressed) paper

Hot-pressed watercolour paper is commonly just called ‘Hot’ paper in the UK, although a few ranges may describe it as ‘Smooth’ instead. Hot paper is so-called because once the paper pulp has been lifted from its vat of water to form a sheet, it is pressed at high pressure between heated rollers that are covered in a smooth felt. This creates a paper surface with a high density of fibres and with very little ‘tooth’, or texture. ‘Hot’ is the smoothest watercolour paper you can buy and is the least absorbent, because the fibres are so tightly packed together. This may make your colours appear slightly more vivid.

The density of fibres in Hot paper also leads to certain other qualities. Because your paint will sit longer on the paper surface with before it soaks in, it is easier to rectify mistakes by immediately lifting off a wash with a paper towel. Your paint colours probably won’t blend together as easily as they would do with a cold-pressed paper, and layers of washes will be more visible. For some this is a positive feature – it really all depends on your painting style.

Who would benefit from choosing Hot paper? Because of its smooth grain, Hot paper is better for painting in greater detail. I prefer this type of paper because I paint small portraits in watercolour, and with a coarser grained paper it would be much more difficult to control my paint with precision. Hot paper is usually the paper of choice for botanical illustrators who also paint in a detailed and precise way, and many other types of illustrators favour it for the same reason (although equally many prefer the ‘arty’ look of a textured cold-pressed paper. Once again, it depends on your style). Hot paper is the best option for mixed media work, for example if you wanted to combine watercolour with graphite, pen or ink.

‘Not’ (cold-pressed) paper

When I first started working with watercolours I wondered what on earth ‘Not’ paper could be! In fact the ‘not’ simply stands for ‘not hot’: in other words, it just means that the paper was cold-pressed rather than hot-pressed. This strange term in only used the the UK, whilst in the rest of the world ‘Not’ paper is simply called ‘Coldpressed’.

Cold-pressed watercolour paper (medium tooth). Photo credit: jacksonsart.com

What also makes Not paper distinct from Hot is that the cold rollers which the paper pulp is pressed through are covered in a much more textured felt, which imprints a coarser surface to the finished paper. This creates that textural ‘artistic’ effect as the washes of paint sink into the coarser tooth and dry with a degree of tonal variation. The strong grain encourages loose and expressive strokes and making Not paper ideal for painting landscapes. Generally speaking the looser your painting style, the rougher the paper texture you’ll likely prefer.

‘Rough’ paper

Rough – or ‘Extra Rough’ – is like an even more granular version of Not paper. It is made by rolling the pulp more loosely through highly textured felt, causing deep pits to be created between the pulp fibres as they are formed into sheets. The textural effects that this surface encourages makes Rough paper particularly suited to landscape painting or to working in bold expressive strokes. Sometimes you may also see it referred to as ‘Torchon’ paper: torchon is a French word meaning ‘rough textured’ and is also the name given in France to a tea-towel.

Rough-pressed watercolour paper (coarse tooth). Photo credit: jacksonsart.com

It’s useful to know that there isn’t any industry standard for the degree of smoothness of Hot, Not or Rough paper and the paper texture within each category can vary considerably between different manufacturers. Additionally, with many paper ranges that produce sheet paper in different weights, the heavier weight tends to be considerably smoother than the lighter weight.

Therefore when trying a new brand of watercolour paper for the first time it may be helpful to visit an art shop in person rather than buying online so you can compare the surfaces of different ranges and decide which you prefer. If you can’t, then some online art stores do offer the option to buy cheap samples of loose sheets of paper. It took me quite a bit of experimentation before I found my favourite paper.

THE WEIGHT OF THE PAPER

Paper will buckle (sometimes called ‘cockling’ or ‘warping’) when watery paint is applied to it, unless it’s of sufficient thickness and has been correctly prepared. Therefore most watercolour paper will be made from sheets weighing at least 300 gsm (grams per square metres). In the US, this is equivalent to 140 lb. Nearly all watercolour paper brands sold in pads or blocks will be at least 300 gsm in weight. A few cheaper brands may be made from lighter paper, and I would avoid these because a paper lighter than 300 gsm will definitely need ‘stretching’ (more on stretching below).

If you want to buy loose sheets of watercolour paper, the weights will vary. 300 gsm is still standard, but heavyweight sheets can be made from paper of 600 gsm. Confusingly, the weights of these heavyweight sheets may often be listed in pounds rather than grams per square metre. You will also see lightweight sheets of less than 300 gsm, but again I would avoid these so that you don’t need to get into the business of stretching your paper

Watercolour board. Photo credit: jacksonsart.com

One last option is to buy ‘watercolour boards’ which consist of a sheet of Hot, Not or Rough paper mounted on to a rigid card. These are up to three millimetres thick (1/8 inch). The advantage of these boards is that not only will they not require stretching but that you don’t even need to tape them down to keep them completely flat as you apply wet washes of paint.

FORMATS FOR BUYING WATERCOLOUR PAPER

Watercolour paper is sold either in loose, large sheets, in glued or spiral bound pads or in gummed ‘blocks’. Sometimes you can also buy packets containing a number of loose small-sized loose sheets. Let’s look at all these options.

Loose paper sheets

Loose paper is sold in large sheets, and can also be cut off a roll for you in an art store. If you buy single sheets of paper online and want it cut down into halves or quarters, some retailers like Jacksons will do this for you for free. Aimed at professionals or experienced artists, loose watercolour paper is generally of high quality and will typically be handmade or mould-made rather than machine-made (we’ll discuss these distinctions further down). Many online art shops sell small paper samples of their loose paper like these below, so you can try them out before investing in a large sheet.

With watercolour paper sizes, a lack of industry standards can again make things rather puzzling. Depending on the manufacturer, it may be sold in either imperial (inches) or metric (centimetre) sizes.

Sheet paper is most often sold in inch sizes. These large sheets will often be termed as either ‘Full Sheets’, ‘Half Sheets’ or ‘Quarter Sheets’. A full sheet is also known as Full Imperial and is 30 × 22 inches, which is a little smaller than the European A1 size. A Half sheet will be 15 x 22 inches, and a Quarter sheet is 15 x 11 inches.

Sheet paper can also sometimes be sold in metric measurements. A common measurement is 55 x 76 cm, which very roughly equates to a Full Imperial sheet. Even when they are sold in centimetres, sheets will rarely be sold in sizes equating to the European ‘A’ size system, such as A1 or A0.

Paper in pads or blocks may be sold in imperial or metric measurements, and in the case of pads it is often available in metric ‘A’ sizes such as A5, A4 and A3. However blocks are not usually available in A size formats.

Paper in pads

Most beginners will tend to start by buying their watercolour paper in a bound pad. Pads are are more economical than buying paper in a ‘block’, although they usually cost more per square inch than sheet paper. When paper is sold in a pad it will always be gummed together or spiral bound on the ‘short’ end. Pads of paper vary in quality from cheap ranges made with wood pulp paper, to the most expensive cotton fibre paper. We’ll discuss these distinctions further down.

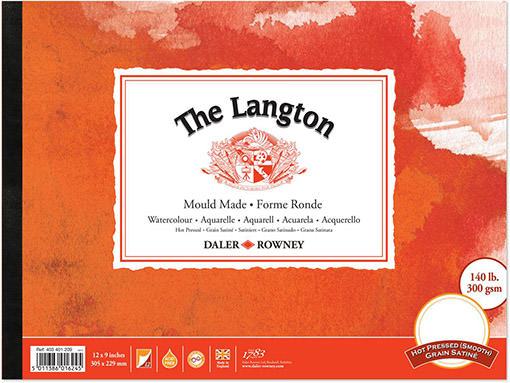

The more expensive the pad, the more likely it will produced in imperial (inch) measurements rather than ‘A’ sizes. For example Daler-Rowney’s professional quality ‘Langton Prestige’ watercolour pads are sold in pads and blocks in a variety of inch sizes, whilst their cheaper ‘Langton’ range is sold in A4 and A3 sized pads. The vast majority of glued pads will be made from 300 gsm paper, although some cheaper ranges may weigh less and are therefore best avoided except for quick sketching practice.

Blocks

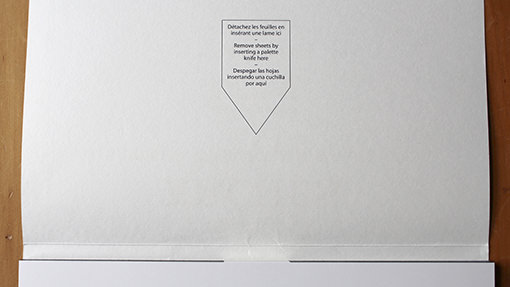

‘Blocks’ are usually made with the higher quality, cotton fibre paper in at least 300 gsm weight. They are available in either Hot or Not finishes, but are not often made with Rough paper because it’s more difficult to bind. The point of buying paper in a block is that the sheets are all glued to each other to keep them entirely flat whilst you work on them. The sides of the pad are coated with a black glue that holds them together all the way around, apart from a small area within along top edge of the pad where there is a little break in the binding.

To use a block, you open your pad and make your first painting on the top sheet of paper. It may appear to buckle a little whilst the paper is wet, but once the paint has dried your paper will shrink back and be perfectly flat again, because it is held tightly to all the other sheets. When it’s completely dry and flat once more you take a palette knife and insert it into the break in the glue binding, and gently lever your painting off (a kitchen knife with a bit of bend in it would work for this too, or a craft knife if you are very careful). You start your next painting on the sheet below, which becomes the top sheet.

Blocks rarely conform to ‘A’ sizes. I think this is because they are most likely to be used by professionals, who would perhaps find the A4 and A3 formats are a little displeasingly ‘letter box’ shaped. However some manufacturers such as Arches offer blocks in a very wide 6″x12″ format for anyone actually seeking a very rectangular shape to paint panoramic landscapes on.

STRETCHING

If you do choose to buy paper with a weight of less than 300 gsm then you’ll need to stretch it before applying watercolour paint. This is particularly important with loose leaf paper, because big sheets will buckle the most when washes are applied to them.

Stretching is done by soaking the watercolour paper in water for a few minutes and then using gummed paper strips to stick it to a flat board such as a sheet of MDF, or a purpose made wooden board from an art shop. If you do want to stretch your paper there are plenty of tutorials online that will show you how to do it. Alternatively you can buy a ‘paper stretcher’ from an art shop to clamp your wetted paper down whilst it dries.

Stretching is likely to result in the loss of some of the paper’s glue sizing, and it just isn’t necessary if you buy paper of a decent weight. Therefore if you’re just starting out with watercolours I’d really suggest that you avoid buying lightweight paper so that you won’t have to worry about stretching it.

Jackson’s smooth panel wooden art board. Photo credit: jacksonsart.com

Even paper with a weight of 300 gsm may buckle a tiny bit when you paint on it, particularly if you apply multiple washes. For this reason I buy my paper in blocks so that it is held conveniently flat. However if you purchase 300 gsm paper in pads, using masking or gummed tape to tape it (dry) to a board or other flat surface whilst you paint should eliminate the problem. If your paper is still a tiny bit warped once it has dried, you can leave it under a few heavy books for 2-3 days to flatten it back again. Some people like to spritz the back of their painting with a spray or moisten it with a brush a little before flattening it under something heavy, and others will iron it at a low heat on the reverse side.

PAPER TYPES AND TREATMENTS APPLIED

Watercolour paper will be made either from cotton fibres, or wood pulp. Occasionally it may be produced from a mixture of the two, containing either 50% of each type of fibre or 25% cotton to 75% wood pulp. Sometimes cotton fibre paper may have linen fibres added for extra durability.

Cotton fibre paper

Paper made from cotton fibres is considered to be of professional grade, due to its strength and conservational qualities. Cotton fibres are longer and stronger than wood pulp fibres and they are completely acid-free meaning that they won’t turn yellow and become brittle over the years. Therefore if you want to sell your work commercially then using cotton fibre paper is really a must.

Because cotton fibres are tougher than wood pulp fibres, cotton paper can better withstand any erasing of under-drawings, multiple paint washes and scrubbing and lifting off paint, without rapid damage to its surface. It’s also generally acknowledged that cotton fibre paper is easier to blend washes on.

‘Wood-free’ wood pulp

Cheaper watercolour paper is made from wood pulp, and this is the type of paper that is usually marketed to beginners or students. In the UK this is sometimes confusingly often described as ‘wood-free’ paper. The name is simply a shortening of the term ‘groundwood-free’. Groundwood is wood pulp that has been broken down mechanically rather than chemically. Therefore ‘wood-free’ means that the paper has been made from chemically bleached pulp.

The significance of this method of production is that when wood pulp is broken down and bleached with chemicals, it removes the ‘lignin’ content. Lignin is the substance within cellulose that holds wood fibres together, but it yellows with age and releases acid. Removing lignins from the pulp also strengthens and whitens the paper.

Whilst these treatments will remove most of the acid from wood pulp, only cotton fibre paper is truly ‘acid-free’ because cotton contains no lignins to begin with. Moreover, when wood pulp papers state that they are acid free, it doesn’t always guarantee that they have been bleached. Some cheaper papers will claim to be ‘acid-free’ or ‘acid-neutral’ simply because they have had an alkali solution added to raise the pH of the paper to neutral. This very type of paper will still yellow over time, and it will also be unlikely to contain the anti-fungals that are added to better quality paper. Only if a paper states that it is ‘lignin free’, or made from ‘archival cellulose’ or ‘High Alpha cellulose’ can you be sure that it’s been properly treated.

What is wood pulp paper like to work on? If you apply multiple washes, scrub at the paint or lift it off the paper you may find that the paper surface will quickly become a bit ‘hairy’ looking as the less durable fibres start to separate. The durability of the paper will also depend on how well it has been sized with gelatin or starch, however. Most people find that paint doesn’t stay manipulable as long on wood pulp paper, and isn’t as easy to blend. If you can possibly stretch to buying cotton fibre paper then you will probably find it more enjoyable and easier to paint onto.

Buffering

If a paper range states that it has been ‘buffered’ this indicates that a chemical has been added to the paper pulp during the manufacturing process to raise the pH and create what is known as an ‘alkali reserve’. This extra alkalinity is a buffer designed to counteract any acid-containing pollutants that the paper may later be exposed. A ‘pH alkalinic’ paper with an ideal pH of between 7 and 8 will therefore be more archival than a ‘pH neutral’ one, so long as it has also been treated to remove its lignins (in the case of wood pulp paper).

Brightening treatments

If you see a paper shade labelled as ‘extra white’ or ‘high white’, this indicates that a little bleach and/or some Titanium Dioxide pigment has been added to the pulp to whiten it. Be aware that contrary to what you might expect even an extra or high white watercolour paper still isn’t really bright white. All watercolour paper is at least a little bit creamy in colour.

You will often notice that the better quality papers are described as being ‘Free from OBAs’. OBA stand for ‘Optical Brightening Agents’. These are chemicals commonly added to paper pulp which can take invisible ultraviolet light and cause it to fluoresce, making the paper appear whiter. However they are unstable and quickly lose their whitening effect, meaning that your paper will change its shade in a fairly short space of time. If a paper range doesn’t describe the product as being free from OBAs, it is fairly likely that these have been added.

HAND-MADE, MOULD-MADE OR FOURNDRINIER PAPER

There are three possible methods for manufacturing watercolour paper. Let’s run through the different types and the quality of paper they produce.

Hand-made

‘Hand-made’ paper is the most straight forward and self-explanatory. Where paper is truly made by hand, the pulp (usually cotton) is immersed in water and a mesh-covered frame and deckle are submerged in the mixture by hand and agitated so that an even layer of the pulp settles on the mesh. This layer is then removed and placed onto another piece of felt, pressed flat and dried. Hand-made paper is often thicker than most other types, is fairly rough in texture and has four lovely deckled (ragged) edges. However it may not be quite as consistently durable as ‘mould-made’ paper because it’s a little more irregular.

Mould-made (also known as ‘Cylindrical Mould’ paper)

Most top quality watercolour paper is ‘mould-made’. This actually involves a fairly mechanised process, whereby cotton fibre pulp is lifted from a stainless steel vat by a rotating cylinder which is covered in a fine wire mesh. The wire-covered cylinder is partly suspended above and partly submerged within the water, and is rotated around in it to pick up a layer of fibres. The layer of fibres is then deposited onto a rotating roller covered in woollen felt which is known as the ‘carrier felt’.

Next the water is pressed out of the pulp and then the sheet is then pressed between some rollers covered in ‘marking felt’. This part of the process defines the eventual texture of the paper. For ‘Hot’ paper the rollers will be hot and the marking felt will be quite smooth, whereas for ‘Not’ paper the rollers are cold and the felt is much rougher. Mould-made paper will have two deckled edges rather than four, and two smooth edges where it is cut from the roll that is produced.

The way that cylindrical mould paper is produced accounts for the difference in texture you’ll usually find between one side of the paper and the other. The ‘felt’ side’ is the side where the fibres were in contact with the woollen carrier felt as they were lifted out of the water, whereas the ‘wire’ side is the smoother side that was in contact with the wire mesh covering the rotating cylinder. It’s fine to paint onto either, but the felt side is technically considered to be the ‘front’ of the paper. This is the side that will carry the maker’s watermark, which is imprinted from a metal seal attached to the cylinder mould. On the ‘wire’ side the imprint of the fine mesh may still be slightly visible and if it’s too pronounced you’ll want to avoid painting onto it because your paint will pick up the grid texture.

Fourndrinier paper

If paper doesn’t state that it is either hand made or mould made then it is pretty certain to be ‘fourdrinier’ paper. Fourdrinier paper is entirely machine-made and is named after the original Fourdrinier machine which was invented for paper making at the turn of the nineteenth century. This type of machine is the cheapest and most automated method of producing paper. It is used only to produce the lowest quality ‘student’ watercolour paper ranges.

On a Fourdrinier style machine the fibre pulp is pushed from the vat of water onto a moving mesh roller. As the pulp travels along the roller, the water is removed and the fibres are aligned in the same direction. The paper is then pressed between felts and dried. Because the fibres all end up facing the same way, machine made paper lacks the lovely texture and strength of mould paper and is prone to distortion when wet.

GELATIN AND STARCH SIZING

Nearly all watercolour paper will come already sized with gelatin. There are also a number of papers sized with starch or acrylic sizes which you can search out if you’re vegetarian or vegan and would rather avoid animal-based products (this post has a list)

Watercolour paper requires sizing to give it some resistance against watery washes, which it would otherwise soak up like blotting paper making it hard to control your paint. Different paper ranges will feel very different to work on depending on whether the size has been applied in either a thin or a heavy layer (known as ‘hard sized’). The more size is added the less absorbent the paper will be, allowing you to remove more of the paint before it has fully soaked into the paper. However if a paper is too heavily sized, the paint may sit on its surface without soaking in enough, making it hard to blend. Some artists actively prefer a paper without much sizing so that the edges of the paint ‘bleed’ and give a fuzzy look.

At least some sizing is essential, as it also serves other functions. Size helps to prevent the paint from cockling the paper, allowing the fibres to sink back into place as they dry so that the paper dries flat. It also helps the paper fibres to absorb moisture more evenly, creating a more consistent colour within a wash. Because sizing allows more of the paint to dry whilst sitting on top of the paper’s surface rather soaking straight into the fibres, it results in your colours appearing more vivid.

The main benefit of sizing however is that it aids your ability to correct mistakes, because when you want to lift off or scrub away an area of paint some of the coating of size scrubs off with it, leaving the actual paper surface beneath intact. It’s helpful to think of paper as really just a lot of tiny fibres stuck together: the more those fibres are agitated by washes, scrubbing or blotting, the looser they will become until the paper’s surface becomes compromised and your paint starts settling in blotches. Size helps to prevent this from happening.

Sizing can be both ‘internal’ or ‘external’. ‘External’ means that size has been applied to the paper after it’s been made into sheets, by soaking them in a bath (sometimes this is described as ‘gelatine tub sized’). ‘Internal’ sizing means that a size was added to the pulp and water mixture before the pulp was turned into paper. Internal sizing gives strength and durability and keeps your colours from soaking in right to the core and losing their vivid quality, whilst external ‘tub’ sizing gives the paper its initial resistance to washes of paint and also helps to protect the surface of the paper. Top quality papers will have both internal and external sizing. Confusingly although most cheaper papers are externally sized only, a few may have just internal sizing instead.

Since different types of watercolour paper have different amounts of size applied either internally and externally or both, they will perform differently from each other. This is why it pays to buy some samples of different paper types if you can and experiment with them until you discover one that you like the best. Note that if you are going to wet and stretch your watercolour paper then some of the sizing will be lost during the process, and so it’s better to go for a more heavily sized paper.

Which make of paper should you buy?

If you are aiming to paint professionally then there’s no question that you need to go for the best archival quality paper, which means cotton fibre and not wood pulp paper. If you are painting just for pleasure then wood pulp paper is ok, but you may want to experiment with different papers until you find one with the right amount of sizing for your painting style. Everyone is different, and different papers will suit different artists.

Stick to 300 gsm paper to make sure your paper won’t buckle, so that you don’t have to go to the trouble of stretching it yourself. If buying wood pulp paper, look for a brand that is mould-made and avoid machine-made paper, because you’ll produce better work on it. Make sure that any wood pulp paper you are considering has had its lignin content removed.

Many companies will make both a cheaper range and a more expensive one, so it’s really a question of choosing a paper range, rather than choosing a manufacturer. For instance both of Daler-Rowney’s standard ‘Langton’ and more expensive ‘Langton Prestige’ papers are both mould-made, but the former is a wood pulp paper and the latter is made from cotton fibre.

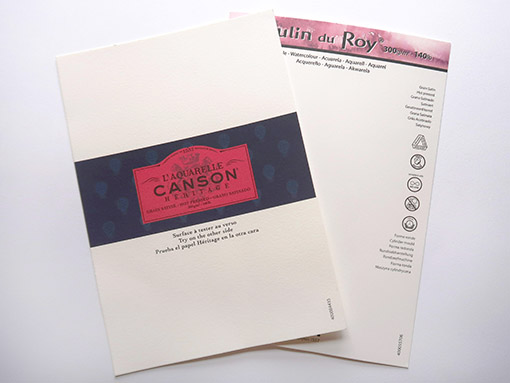

Winsor & Newton also make two mould-made ranges: their ‘Classic’ range which is a wood pulp paper and their ‘Professional’ cotton fibre paper. Canson’s ‘Moulin de Roy’ is a cotton cylinder mould paper which is internally and externally sized. Canson’s Heritage L’Aquarelle’ is also a very good cotton paper but it is externally sized only and is slightly cheaper.

A very good manufacturer is the long established ‘St Cuthbert’s Mill’ who make very famous papers called ‘Saunders Waterford’ and ‘Bockingford’, both of which are mould-made. The Saunders is a cotton paper and is both internally and externally sized, whilst the Bockingford is made from wood pulp and is internally sized only.

Other very reputable paper makers include the French mill Arches (pronounced ‘arsh’) who make a famous paper called Aquarelle, and the Italian company Fabriano who produce my favourite paper, Fabriano Artistico. I’ve put together this handy list of available watercolour papers, which compares their methods of manufacture, availability in different formats and the type of sizing used.

CATEGORIES

DRAWING PEOPLE

DRAWING ANIMALS

DRAWING MATERIALS

OIL PAINTING

WATERCOLOUR

PAINTING MATERIALS

FRAMING